I see a lot of misconceptions about space in general, and space warfare in specific, so today I’ll go ahead and debunk some. In the process, we’ll go through the moment to moment of space warfare itself.

Zeroth misconception, no, there won’t be stealth in space, let alone in combat. It is possible through a series of hypothetical technologies or techniques, but it won’t be possible for any reasonable spacecraft under reasonable mass and cost restraints.

Now then, on to the first real misconception. Wouldn’t missiles dominate the battle space, being fired from hundreds of thousands of kilometers away? Wouldn’t actual exchange of projectile weapons never happen in reality?

The answer is no, actually. There is a prevailing hypothesis that missiles will soon be the only relevant weapon on the battle space, and it is likely borne out of current trends in modern warfare. ATGWs are already starting to upend tank warfare, and Anti-ship missiles are doing something similar to naval warfare. Indefinitely extrapolating this trend would lead one to conclude warfare will soon be nothing but people sitting in their spacecrafts launching missiles at one another.

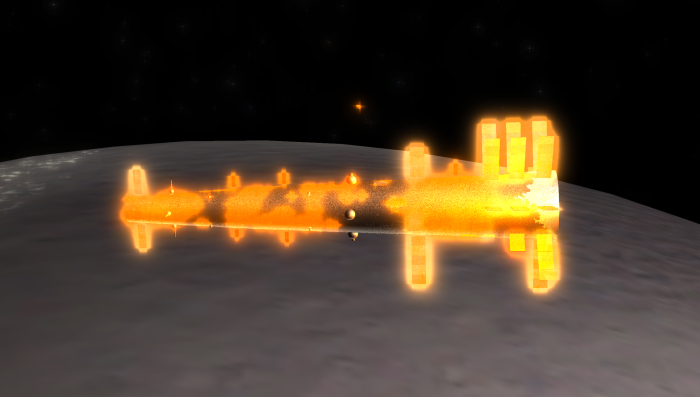

But this is not true. CIWS point defense systems are already starting to shift the balance away from missile strikes. As suggested in an earlier blog post, military strategists are even beginning to suggest the development of CIWS systems may bring naval warfare full circle, all the way back to World War I battleship warfare. This isn’t to suggest that missiles are useless. Indeed, enormous salvos of missiles are effective at overwhelming CIWS systems, and they are in game as well.

Yet we begin to see the limitations of each system. Point defense systems, railguns, coilguns, conventional guns, or even lasers, are power limited in this exchange. There is a finite amount of power to use when firing, except for conventional guns. Conventional guns suffer from low muzzle velocities, and high muzzle velocities are crucial to intercepting missiles coming at you at greater than 1 km/s. This power limitation is what prevents these point defense systems from being impervious to missile salvos. Power consumption is limited by radiator mass actually, as simply slapping down more nuclear reactors is easy, but trying to deal with the added mass of all the radiators needed to cool those reactors is much more difficult.

Missiles, on the other hand, are also limited by mass. A hundred-missile salvo is sure to overwhelm any point defense system, but the amount of mass this requires the launching ship to take on is enormous, and will kill its mass ratio. In the end, it turns out the Rocket Equation governs just how effective missiles and point defense systems are. In game, the systems ended up surprisingly balanced, with neither being a dominant strategy, with either being more effective in certain situations, and weaker in others.

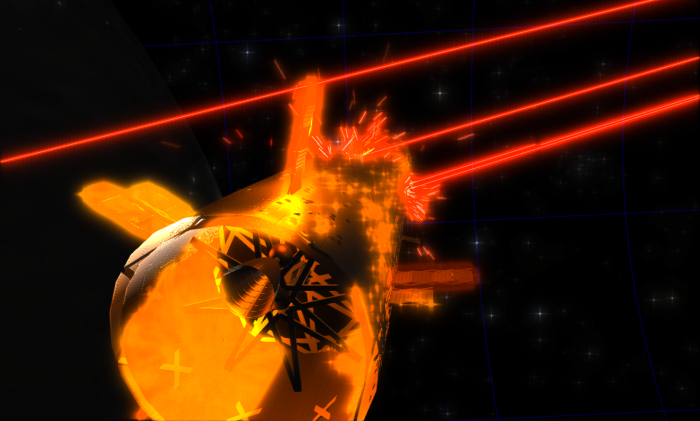

Next misconception, wouldn’t lasers dominate the battle space? Lasers do not suffer from many of the inaccuracy problems that projectile weapons do, and move at the speed of light, so they are literally impossible to dodge. So lasers are the king of the battle space, right?

Wrong. Lasers suffer from diffraction. Badly. The power of lasers in space drops painfully fast with distance, and frequency doubling only ameliorates the issue slightly. Lasers are notoriously low efficiency compared to projectile weapons. But that’s not the main issue. When comparing hypervelocity projectile impact research with laser ablation research, one discovers a stark contrast in their efficacy. Laser ablation is simply less effective at causing damage than projectile impacts. Whereas hypervelocity projectiles cause spallations and cave in armor effectively, laser ablation is poor, with energy wasted to vaporization, radiation, and heat conduction to surrounding armor. On the other hand, at very close ranges, where diffraction is not an issue, lasers outperform projectiles easily. Unfortunately, nothing aside from missiles will likely ever get that close, and even then, they will likely be within close focus ranges for milliseconds at most.

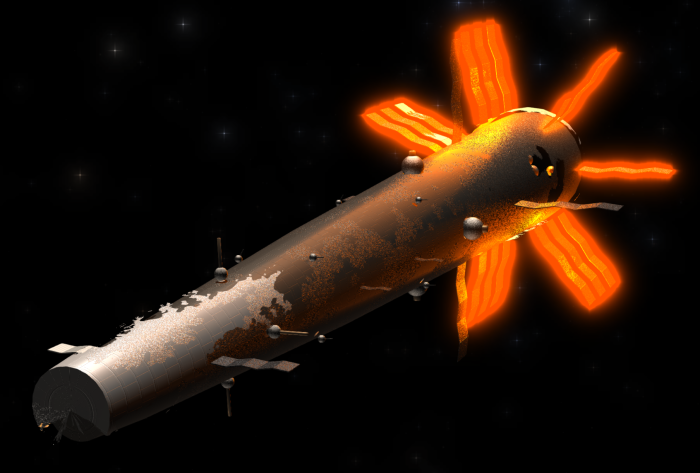

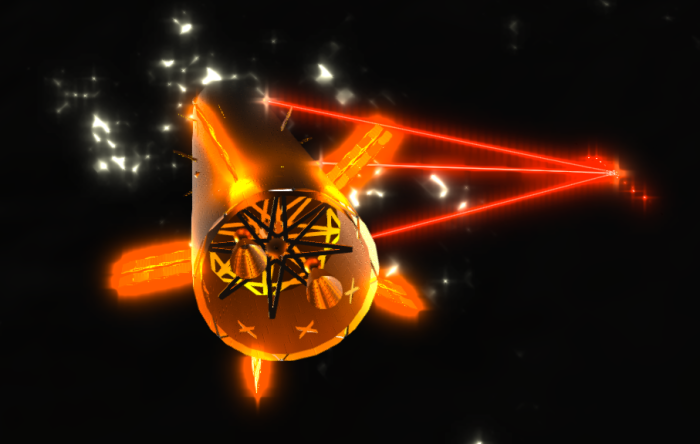

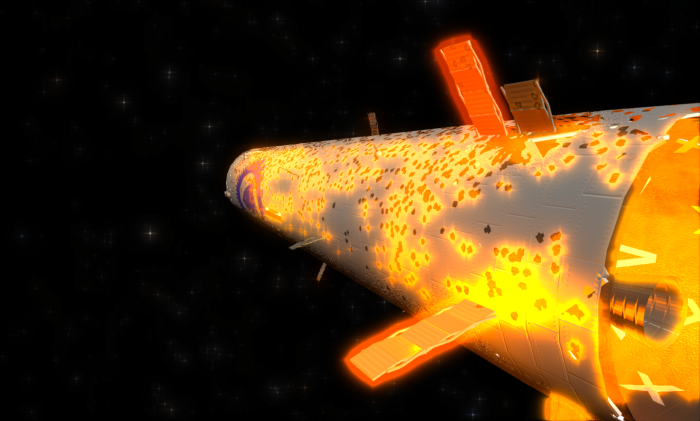

Lasers still useful at long ranges, though. Lasers fill a very specific niche in space warfare, and that is of precision destruction of weakly armored systems at long distances. Lasers are very good at melting down exposed enemy weapons, knocking out their rocket exhaust nozzles, and most importantly, killing drones. While missiles have very few weak points, and can shrug off laser damage with thick plating, drones have exposed weapons and radiators, which makes them very vulnerable to lasers.

In terms of actually destroying enemy capital ships, however, lasers can cut into the enemy bulkhead all day with basically zero effect (I measured the ablation of a monolithic armor plate at one point, and found that the ablation was happening at micrometers per second).

Final, misconception, wouldn’t computers just control everything in combat?

Yes and no, but mostly no. CIWS systems are already computer controlled, and all weapon aiming is similarly already controlled by the computer in game. Anything that has easily computable maxima are solved by computers in game. But there are numerous choices in combat which have no obvious local maxima, and these require human decisions. In other words, you the player and commander need to make these choices. As it turns out, the right or wrong decision can mean the difference between victory and failure.

In game, you won’t be aiming any weapons and firing them, nor will you be flying drones around. The computer can do both better than you, and so the computer will be in control of these things (besides, do you really think you could effectively aim at a speck of light 50 km away moving at 1 km/s at you?).

What you will have control of are the higher level strategic decisions. The orders you give your missiles, drones, and capital ships are crucial decisions you must make in combat. Will you send your missiles in a beeline at your enemy, or perhaps order them to spend valuable delta-v dodging enemy point defense fire? Should you retract your radiators to reduce your heat signature to avoid enemy missiles, and risk the loss of your firepower for the precious few seconds? Should you hold your drones in reserve, close to your carrier, or send them guns blazing as the enemy capital ships approach?

Also as well, one of the critical choices you can make is what to target of the enemy. Each subsystem of every enemy spacecraft is simulated in real time. The reactors draw power, the radiators expel heat, the turrets and guns drain power, all in real time. If you want to disable the enemy’s ability to harm you, the obvious choice is to go for the weapons. But weapons are small, hard to hit unless you have a laser. Going for the enemy’s radiators might be an alternative strategy, with radiators being large, easy targets, although radiators, once armored, are surprisingly sturdy. Not remotely as strong as monolithic armor, but still able to take a reasonable beating of projectile and laser hits. Of course, maybe taking out of the enemy’s engines is more your style, the rocket nozzles being flimsy and poorly armored to allow them to gimbal easier. Plus, a ship that can’t move or dodge is a much easier target.

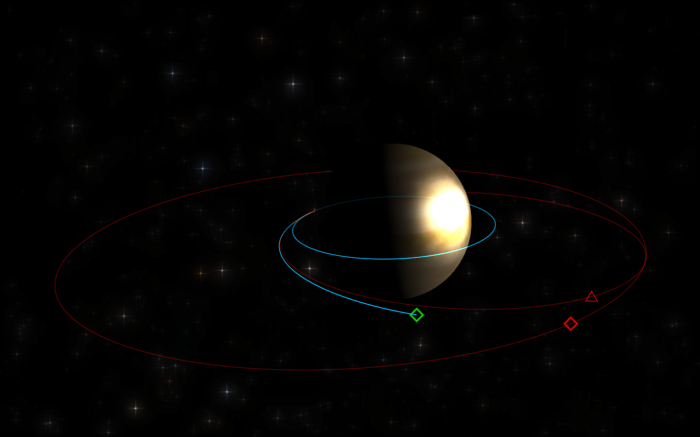

But most importantly, orbital mechanics are king in Children of a Dead Earth. Indeed, orbital mechanics are the core mechanic of the game, even, counterintuitively, in combat. Once you reach weapon range, orbital mechanics lose most of their relevance, but everything up to that point hinges on orbital mechanics.

Your incoming speed and angle of attack entering combat, two critical attributes which govern how the combat unfolds, are determined entirely by your ability to use orbital mechanics to your advantage. How near or far you are from the nearest gravity well (planet, moon, or asteroid) has a huge effect on combat speeds. Additionally, evading the enemy before even entering combat is a big part of the game. If you can drain the enemy’s delta-v through effective orbital mechanics, they may fight at reduced effectiveness in combat. If you’re good enough, you might be able to run them out of delta-v entirely, and never even have to enter combat at all!

That’s all for now. Next time, we’ll dig into the science of the rockets themselves!

Looks really cool!

Regarding anti-missile systems, I think that it’s important to realize that at longer ranges that can be very effective by merely blinding or superficially damaging the weapon. Closer in, they need to entirely vaporize the missile since as a KE weapon, given an intercept trajectory, it’s going to hit unless the target is accelerating, and such that it moved at least a cross-sectional radius during the remaining flight time of the now unguided KE weapon. You can obviously look at the time required to cross from CIWS range to the target and compare to the capability of the target to move out of the way… CIWS might require using RCS or burns to hit incoming targets, then make sure the ship moves outside of the path of the missile debris.

If KE weapons are armed with a sort of self-destruct, such that if blinded/damaged they break into pieces explosively, then the target might be showered in fragments that still have a decent relative velocity.

LikeLike

Right, dodging an unguided projectile can be exactly calculated based on target acceleration and areal cross section versus the projectile trajectory. In space, dodging is rather easy, as the capital ships tend to have accelerations in the milli-g0 ranges, and there is nothing in the line of friction to slow them down. This, along with their narrowed cross section, necessarily forces projectile weapon combat to happen at somewhat close ranges (tens of kilometers), though missile warfare has no such limitation.

And yes, kinetic shrapnel missiles remain very effective even after broken in pieces.

LikeLike

A special kinetic shrapnel missile was discussed in the Spherical War Cow blog, being called the ‘Soda Can of Death’. Launched on a missile bus, dozens of intelligent ‘cans’ are released half way to the target. They form an intelligent network, sharing targeting information and have some limited maneuvering capability.. Shortly before impact a fragmentation charge detonates to hit the target with a grape shot, penetrating the target’s Whipple shield. This approach shall saturate the defenses, while still being able to hit a maneuvering target.

Concept graphic at http://francisdrakex.deviantart.com/art/The-Soda-Can-of-Death-424421427

LikeLike

“…military strategists are even beginning to suggest the development of CIWS systems may bring naval warfare full circle, all the way back to World War I battleship warfare.”

I’m pretty sure WWI battleships were themselves the product of millennia of naval warfare development. Unless CIWIS systems bring naval warfare to the point that ramming and boarding become major naval tactics, naval warfare would just have gone in a little loop-de-loop.

LikeLike

It will still be a full circle, there will just be a path leading up to it from before.

Also, there is that one mission in game where boarding is a legitimate tactic (the one with the mutinying crew, I forget the name).

LikeLike

…I’m not sure you understood my comment.

Unless something after the resurgence of battleships leads to boarding, it will be a loop-de-loop…and even in that case, stopping off in intermediate stages means that doctrine would be going in reverse, not in a circle. Going full circle would be going from the newest to the oldest, possibly followed by going through new versions of the stages.

And I’m not talking about the game. I didn’t mention it once in my original comment.

LikeLike

“CIWS point defense systems are already starting to shift the balance away from missile strikes”

May I be so bold as to suggest a major correction? It’s a common misconception that CIWS (especially gun-based) is so effective. Between long-range AAW missiles (SM-2, SM-6), medium-range AAW missiles (ESSM), and EW, gun-based CIWS is by far the least capable: shortest range, fewest stored kills, and lowest Pk against maneuvering supersonic/hypersonic/ballistic AShMs.

Even assuming perfect targeting, each mount can only consummate a few engagements before running dry. Even assuming Ph=1 per salvo, there was doubt whether the Phalanx’s 20mm shells would reliably neutralize missiles, especially the larger ones commonly used by Soviet naval aviation and surface forces, some of which were partially armored. Even if Phalanx disables the missile, unless it detonates the warhead, inertia alone is liable to carry the missile debris (warhead, remaining fuel) into the ship, especially at the very short CIWS operates.

Many gun-based CIWSs are now being replaced by missile systems, eg SeaRAM/RAM (RF/IR terminal and 11 or 21-round magazine), which have greater range, deeper magazines, higher Ph, and higher Pk.

Yes, many gun-based CIWSs are still in service in fleets around the world. But that’s owing more to their low-cost, low footprint (no deck penetrations), incumbent status (commonality, pre-existing integration, logistics and training), and lack of pressing need for most navies, rather than a sign of their effectiveness.

Naval lasers and railguns, even in their PRE-operational capacity, are already shaping planning to a much greater degree than gun-based CIWS. Thanks to their high Ph, deep “magazines,” favorable cost-exchange, and especially short TTT, lasers and railguns may significantly improvement leaker-management, potentially enabling a much more efficient SLS shot-doctrine, effectively doubling stored-engagements, and thus growing the maximum acceptable raid size (assuming sufficiently capable targeting), while also (affordably) increasing endurance against harassing attacks intended to attrite missile stocks in preparation for mass-raids.

If anything, USN missile-defense doctrine is becoming MORE missile-heavy, not less, as it moves to a denser net of medium-range missiles (ESSMs) for the balance of its interceptors, not CIWS (gun- or missile-based).

In potential USN engagements against peers/near-peers in the near-mid future, naval air and missile defense will more closely resemble WWIII ca 1985 (where USN surface groups had to contend with salvoes of potentially hundreds of AShMs at a time) rather than the languid 1990s/00s where the American hyperpower had virtually no competition at sea.

Naval air and missile defense will be missile-dominated for the foreseeable future. As far as I’m aware, no blue-water navy anticipates otherwise.

LikeLike

Counterpoint: CIWS guns are limited by range. In space, you may shoot quite far, your weapon can engage a target at 10km with the same (almost) muzzle velocity you began with. There is also no radar horizon, just range.This means that theoretically you can make a try at considerable range.

Further, fratricide could come into play, one or two out of a salvo might go up just from friendly fire.

I have the feeling that missiles also might have the problem of evasive action being more limited, due to fuel constraints.

Though this is limited extrapolation…

LikeLike

“It’s a common misconception that CIWS (especially gun-based) is so effective”

On tanks “CIWS” (named APS, Trophy for example) are effective enough. Of course, antitank missile is not so fast as AA or space, but it work from extremely short distanse – 1-2 kilometers for infantry systems. In space CIWS rounds will not influenced by atmosphere and incoming missile can maneuver only by trusters – situation for CIWS should be better than on Earth.

LikeLike

If you are measuring ablation like this, something in your assumptions of how it’s supposed to work is wrong.

Lasers have two groups with distinctly different mechanisms of damage:

‣ Pulse. They dump much heat very fast, this causes ablation of a very thin layer, and recoil from explosive vaporization sends a shockwave into the target. A thin shell can be hammered in, thick may suffer from spalling, cracks propagation, shattering of fragile parts and whatnot (much like HE-SH hit – the shock is sharper, but probably less energetic).

‣ Continuous (well, in practice quasi-continuous with weak high frequency pulses, but the point is, they burn on and on). They simply transfer heat into focal spot. Hopefully, melting it after a little while, but even if not (cannot maintain the heat because the target rotates, etc), at very least it can wreck the heat balance of smaller targets (missile/drone) badly, both directly and by “clogging” radiators (in that it’s more inefficient to pump heat into already hotter things).

With correct effects, estimated (e.g. “Weaponry in space: the dilemma of security”) amount of energy on target necessary for a mission kill is about the same for all weapons, provided the armor is just solid material rather than specifically made to defeat something in particular. The latter, of course, is the real problem with lasers, because “coat everything with micron-thin low albedo metal film” is easy on mass budget, while “make thick layered armor” isn’t.

X-ray lasers, in addition to better range, have heat and modest penetrating effects, and could even cause local EMP effect much like x-rays from a nuke, but of course x-ray lasers are so tricky, they make neutral beams look promising. Even after those sharp-angle mirrors were designed and tested.

LikeLike